Everything You Wanted to Know About the Debt Limit Fight But Were Afraid to Ask

Q&A on the LSGA

House Republicans released their highly anticipated debt limit bill on Wednesday (summary here), with the intention of floor consideration under a closed rule next week. While readers of this space should be familiar with the basics, it should be noted that the United States reached the federal debt limit on January 19, meaning the Treasury Department can no longer issue the ongoing debt it needs to sustain the structural deficit within the federal budget. Treasury is currently using “extraordinary measures” to maximize the length of time before government obligations eclipse incoming revenues, but absent congressional (or executive) action, the United States is poised to run out of cash sometime this summer.

Below I try to tackle the basics of where things stand, what might happen next week, and where things go from there.

What’s in the Republican debt limit bill?

The Limit, Save, and Grow Act pairs a roughly one-year debt limit increase with measures that fit those three categories:

Limit: The bill sets discretionary spending levels for the next 10 years, calling for a return to FY22 spending levels (a $130 billion cut from FY23) and limiting growth to 1 percent each subsequent year through 2033.

Save: In addition to the discretionary spending caps, the bill calls for hundreds of billions of dollars in savings by rescinding unspent COVID funds ($50 billion), nullifying President Biden’s student loan debt forgiveness plan ($465 billion), and repealing the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA)’s clean energy tax title ($271 billion) and its funding for the Internal Revenue Service ($71 billion.)

Grow: The bill makes various reforms to the terms of federal welfare programs, applying and expanding work requirements to TANF, SNAP, and Medicaid. It also incorporates the REINS Act, a longtime regulatory reform priority of the GOP, and H.R. 1, the Lower Energy Costs Act, the energy and permitting package the chamber passed in March.

Can it become law?

No. This package is best thought of as an omnibus vehicle for GOP policy priorities, political sugar to help the medicine of a debt limit lift go down. If a provision added votes to help House leadership get to 218, it was included. It is not expected, nor intended to become law, and should be analyzed with that in mind.

Some elements of the package have better prospects than others, be it within a debt limit deal or on their own:

Rescission of unspent COVID funds–This one is the lowest of low-hanging fruit and likely happens in any event. Reprogramming unobligated spending is a favorite budgetary gimmick in these situations.

Permitting Reform–The inclusion of H.R. 1 can be seen of something of an olive branch, the one area of the bill that could lead to a win-win. But negotiating the policy particulars of a permitting package will be tricky enough without the pressure cooker of a debt limit negotiation, and this is something Republicans don’t need legislative knife-point to achieve. Decent chance of eventual passage, but almost certainly outside of the debt limit context.

Nullification of Student Loan Forgiveness–This one seems exceedingly unlikely as a political matter, but given its uncertain fate in the courts, it could be less practically painful than some other cuts sought by the GOP.

What about IRA repeal?

Dead on arrival. In fact, the package did not initially include repeal of any IRA tax provisions, with leadership citing its reluctance to send the Senate a revenue vehicle. It wasn’t until an 11th hour demand by the House Freedom Caucus that repeal of the IRA clean energy title was incorporated into the bill. With zero appetite for repealing IRA policies in the Democratic Senate, a bill with such provisions will not get near the President's desk, and if it somehow did would be swiftly vetoed. Nonetheless, expect stakeholders to make a big push to defend these policies as a means of reminding Republicans that these provisions have strong business support and a robust red state/district footprint.

So why did they do this?

Since their initial meeting at the White House in early February, Speaker McCarthy has been unable to engage President Biden in further talks, with Biden plainly stating he would not negotiate over the debt limit, and would only discuss spending after Republicans release their budget. On the heels of a McCarthy speech at the New York Stock Exchange meant to sound the alarm to Wall Street, Republicans released this package as a means of establishing a consensus House negotiating position, and forcing the President to the table.

Is the White House’s refusal to negotiate a tenable position?

From the standpoint of the White House, the current posture makes sense for three reasons:

Why bail Republicans out if they can’t get their act together? Make them demonstrate they can be a functional majority.

To the extend they trust the Speaker to bargain in good faith, what’s it worth if he can’t be counted on to corral the votes? Make this leadership team demonstrate their ability to whip.

Unless Republicans display a willingness to vote for a debt limit increase—even a conditional one—who is to say that default on Biden’s watch isn’t the goal? Make them show that they’re looking for a productive offramp.

That’s the calculus today. Whether it continues to make sense depends what House Republicans can muster next week.

In the end, for the “clean increase, no negotiations” position to be sustainable, Biden must be prepared to either outlast the political will of Republicans, or use some novel executive action (more on that later.)

What happens if they pass the bill?

That’s up to the White House, which has so far insisted that it would be unmoved by House passage. Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer followed the President’s lead, saying that the bill would not be taken up in the Senate and that Democrats will only accept a clean increase. However, congressional Democrats are already getting anxious over the absence of talks, and with a volley from the GOP House putting the ball back in the President’s court, there would be increased pressure to engage. Meanwhile, House Republicans are framing this vote as the ticket that gets Speaker McCarthy a seat at the bargaining table.

What happens if they fail?

Whether they fall short or pull the vote entirely, GOP leadership would suffer an embarrassing if not entirely shocking defeat, one that would surely draw recriminations within the conference, ending whatever nominal honeymoon McCarthy’s speakership has enjoyed. The White House would be further emboldened, and likely dig in on its insistence on complete and total surrender by Republicans. With House dysfunction taking McCarthy out of the game, all eyes would move to the Senate. While Schumer would follow Biden’s lead, one would expect a centrist “gang” to emerge to explore what the 60-vote market could bear.

What could the endgame look like?

Short of the unlikely (and messy) capitulation of one side, resolution of the current impasse will require a strategically ambiguous and plausibly deniable connection between the debt limit increase on one hand and a budget deal on the other. It is fairly simple to imagine the terms of a deal both sides could live with in aggregate, but President Biden can’t be seen as having paid a ransom to Republicans on the debt limit, who in turn can’t be seen as caving to Biden on a “clean” increase.

For all his insistence on an unconditional debt limit bill, the President has clearly and repeatedly signaled his willingness to negotiate on the budget. Given the reality of divided government, he has little choice but to make concessions on this side of the ledger. While it may seem like semantics, the distinction between these two tracks–debt limit versus spending/budget–is the best way to square the circle, providing a permission structure for Biden to engage, and both sides an opportunity to save face.

Can the House use a “discharge petition”?

Early coverage of the issue centered around this procedural tool as the “easy button” that could elide a blockade by GOP leadership against a clean debt limit bill. There were and are a variety of problems with this idea of discharge as a panacea:

Cumbersome process–It’s not as simple as introducing a bill and lining up support. The bill must be referred to committee and toil there for 30 *legislative* days before a motion to discharge can be filed. Once the petition has the signature of 218 members, it can be moved to the discharge calendar, triggering another seven legislative day wait before a member can notify the House of their intention to offer the bill, which could then be offered within two legislative days at the discretion of the Speaker.

Would have to be baked in advance–This is a rigid, slow-moving process that is ill-equipped to deal with a fluid, dynamic negotiation. One would have to settle on the size of the increase along with any other conditions before the bill could be filed, thereby starting the clock. To date, neither party, nor any caucus or enterprising individual member, has released more than a vague framework of what they want, including the scale/length of a clean increase. [Edited: One clever way around this problem would be to leave a placeholder to be filled later in the process via amendment. h/t Ringwiss]

Probably too late–With no clean debt limit bills yet filed with this process in mind, the earliest you could see a bill ripen for discharge would be late June/early July if it were filed today. [Edited: The wise Ringwiss pointed out the flaws in my original math.]

Doesn’t have the votes–Despite reporting centered around the most conservative faction of House Republicans, there is zero GOP support (in either chamber) for a clean debt limit increase. While there are divisions over what Republicans would settle for, they are united in demanding some sort of concession. While this resolve could dissipate as the pressure ramps up, the timing hurdles make it impractical for a last-minute option. Perhaps most importantly, for the time being, a clean debt limit bill could not even pass the Democratic Senate.

Seldom successful–The last time a bill was discharged and passed by the House was Ex-Im Bank reauthorization in 2015. [This measure was uncontroversial outside of the House GOP, and was easily folded into the highway bill later in the year.] The last time a discharged bill became law was the McCain-Feingold campaign finance law in 2002.

Will the McConnell save the day?

Some onlookers have pinned their hopes on the Republican Leader, for his reputation as a keen strategist and his record of working out high-stakes bipartisan deals, including with his former Senate colleague Joe Biden. Recently returned to the chamber after an injury, the Leader is content for now to let McCarthy and House Republicans take the lead and wish them well. Even if/when the action shifts to the Senate, it is more likely to be a middle-out entrepreneurial effort without the blessing of Biden. For his part, McConnell is not eager to jump back into the fray after a rocky experience during the last debt limit standoff in 2021, one that President Trump has repeatedly seized on in his spat with the “Old Crow,” another reason for the delicate dynamic. The Republican Leader will be instrumental in blessing whatever Republicans will abide in the Senate, but his direct involvement, should it materialize, is a ways off.

Can the government use prioritization?

Many Republicans and even some Wall Street analysts have posited that the Treasury can and should prioritize their payments in the event of a debt ceiling breach in order to avoid the most painful elements of a default scenario. There was even a short-lived effort to pass legislation to that effect, primarily as a messaging exercise. As a practical matter this is very likely a contingency that Treasury would have to prepare for, but the system is complex enough that it would not be nearly clean as proponents imply. With federal revenues only making up roughly 75 percent of outlays, picking and choosing which programs to fund is simply not a sustainable solution. De facto prioritization may occur, but the choices will be brutal, and at best it buys Congress a bit of time.

Can Biden act unilaterally?

This is the $64,000 question, and a willingness to consider such options (or the perception there of) may be what buttresses their firm no-negotiation stance. While there is no precedent for the executive branch acting in such a manner, this administration has not been shy about testing the limits of its authority, and they are surely taking inventory of the theoretical tools (and novel arguments) they have in their arsenal.

There are various theories of how a President could elide the debt limit, such as the minting of trillion dollar coins, or invoking the primacy of the public debt clause under the fourteenth amendment. The Congressional Research Service, Capitol Hill’s internal think tank, looks at the lingering legal questions around those approaches here. But perhaps more than the legal uncertainty, the viability of executive action may rest on how markets would react.

If nothing else, these moves could buy time, even as they set of high stakes legal and political battles.

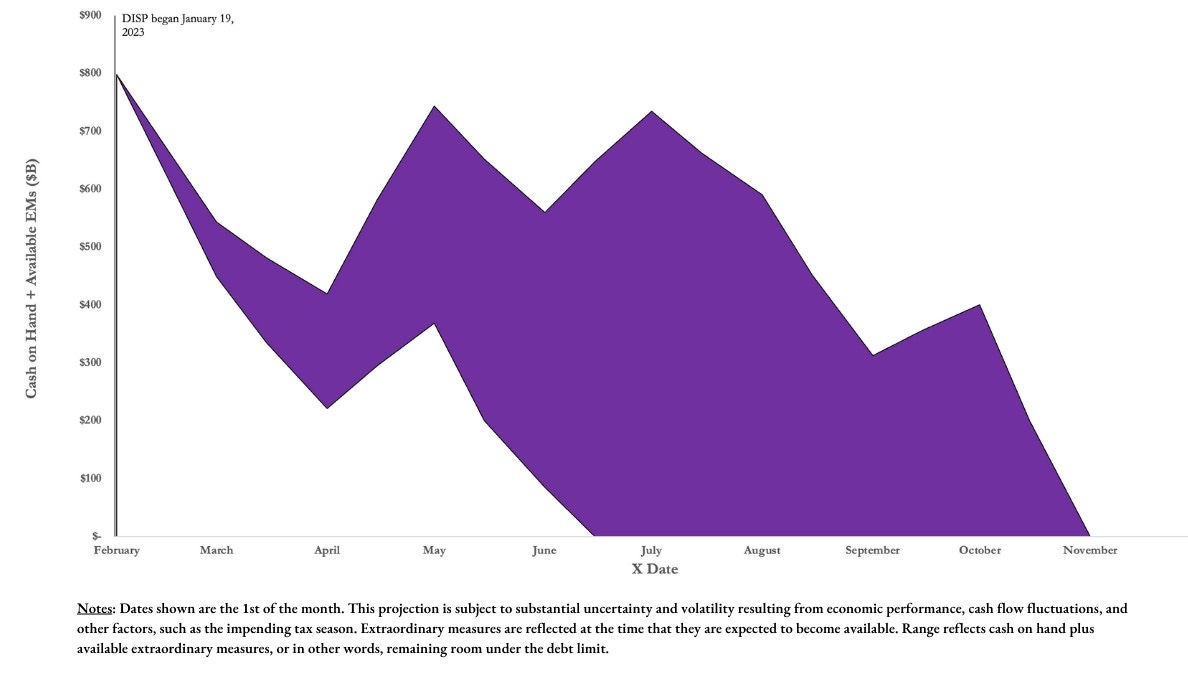

What is the likely X-date?

Depends who you ask. The most recent Congressional Budget Office (CBO) report projected it to fall between July and September. Using CBO data, the Bipartisan Policy Center identified risk in the early part of June, stretching into late July or beyond if receipts carry us beyond June 15. In the interim, further pressure from the banking sector turmoil and lighter-than-expected tax revenue have led more analysts to peg the second week in June as the fulcrum. In any event, the X-date is poised to occur well before the September 30 end of the fiscal year that serves as the deadline for government funding.

What is the best case scenario?

If we define the best case as the most orderly possible resolution, it hinges on the success of the House GOP package. Once the ball is in Biden’s court, he can either open up a parallel negotiation on the budget (don’t call it a debt limit talk!), or stick to his guns and stare Republicans down.

The former is reasonably straightforward: a negotiated cap on FY24 spending (and perhaps beyond) is inevitable–the alternative is a CR which amounts to a de facto freeze. COVID fund rescission and perhaps a fiscal commission are also ready-made fig leaves that the White House should be able to palate. A short-term increase would be useful both as a good faith gesture, and as a means of syncing up the X-date with the government funding timeline.

The latter only works seamlessly if he is prepared to mint the proverbial coin. [Ironically, this could be the most desirable outcome for Republicans–sparing them from supporting a compromise package, and giving them fodder for political attacks.]

What is the worst case scenario?

House Republicans fail to pass anything next week, confirming Dem suspicions, and affirming Biden’s decision to hold out for a clean bill. Gang-related activity in the Senate fails to bear fruit, with Schumer holding the line among the caucus rank and file. Calendar constraints render the discharge route moot. A somnambulant Wall Street continues to believe that Congress will figure it out like they always do.

Absent pressure from the markets, both sides dig in, believing the other has more to lose. Tax receipts continue to come in light, setting up an early June reckoning, and an attempt at a short-term increase fails, dividing the GOP and reinforcing the White House’s instinct to hold out for total and complete surrender. Markets belatedly wake up to congressional paralysis, and the turbulence sets off a scramble among moderates to craft a last minute deal.

Pressure builds on House leadership to put a “skinny” debt limit bill on the floor in a bid to gain leverage. The House Freedom Caucus pushes prioritization language, insisting that the government must live within its means. Before any vote can materialize, President Donald Trump weighs in on Truth Social, blaming RINOs for the GOP’s struggles, and exhorting Republicans to “play ‘tough’! be smart! FIGHT! And win big.” A divided majority again fails to pass anything.

The battle becomes a test of political pain thresholds, with either side believing the other will tap out first. Eventually somebody blinks, but not before a credit downgrade, untold billions in lost wealth, and trillions in long-term costs. The debt limit is ultimately lifted–for now–but nobody comes out better off, nor with any lessons learned.

So are we doomed?

No! The problem with most of the debt limit takes to date is that they fall into one of two camps. Either they begin with the premise that default is unthinkable and work backwards to explain how everything will turn out fine because it always does; or they determine that default is inevitable and there’s nothing we can do. The glib happy talk is as self-defeating as the doom and gloom is self-fulfilling. What’s important is that all parties involved—including Wall Street—appreciate the gravity of the situation and the seriousness of the respective positions, with an understanding that there’s room for everyone to save face. As long as Republicans and Democrats can get out of their own way, there’s no reason this has to go off the rails.

If you liked this post, make sure you check out my podcast, The Lobby Shop. For our most recent episode we spoke to Machalach Carr, General Counsel to Speaker Kevin McCarthy, about the role of congressional oversight, and how it informs the GOP agenda in the 118th Congress. Listen and subscribe here.

Fantastic Debt Limit summary.

Best article I have read so far on the "Debt Limit." Give it a read while you can. A masterpiece. I say, enable SNAP et al. intact without restrictions for college and technical school students and go hard after clean energy IRA spending and build up the issue for leverage, even if IRA is popular with those corporations schilling; in on the green energy scheme. Republicans need to become moderate on social issues and I have no problem with student debt forgiveness. Education is a net positive for our economy while green energy will destroy a so called free market economy, based on government mandated energy transition materials that are less in abundance than oil and gas. Solar, wind and electrification of vehicles will collapse our economy, and a cover up will further ensue, mark my words.